The Show That Ate Democracy

Politics has always borrowed from theatre, but what we are seeing now is something different: a politics conceived as performance and sustained by it, where spectacle no longer serves the agenda but often stands in for it.

ANALYSIS

It is the archetypal populist stunt: Argentina's presidential hopeful Javier Milei brandishes a chainsaw aloft at a rally in Buenos Aires. At first glance, it appears as little more than his trademark eccentricity, a theatrical flourish designed to electrify the crowd. Yet within the imaginary of performative politics, props are rarely arbitrary. The object frames his political project across several registers at once: it crystallises Milei's promise to "cut through" bureaucracy, dismantle the state apparatus, and free Argentines from the burdens of debt, inflation, and corruption.

At the same time, the object works on the register of the body. It condenses the disgust of so many of his compatriots with a system that has ceased to serve them. Watching the scene, one can almost hear the chorus rising from living rooms across the country: yes, tear it all down! Digital culture multiplies these affects exponentially: in an environment where circulation thrives on memes and fragments, Milei’s theatrics move as condensed affective packages, travelling faster and embedding more deeply than any programme or manifesto.

The violence of the gesture feels surgical: it cuts into the body’s reservoir of pent-up rage and releases the intoxicating promise of destruction that might, eventually, make space for something new. For the French psychoanalyst and philosopher Jacques Lacan, building on Freud’s metapsychology, this impulse belongs to what he called the death drive — a compulsion to repeat that circles its object without ever reaching satisfaction. The result is not catharsis but "jouissance": an excess of pleasure tipping into pain, a thrill that destabilises rather than resolves. The chainsaw offers no futurity, no plan for what comes next; it remains suspended in the pure circuitry of feeling, a loop of intensity without end.

Politics as Performance

Theatre scholar Milija Gluhović and colleagues remind us in The Oxford Handbook of Politics and Performance that "all politics is performative, performance is political." While this has always held true to some degree, the claim no longer captures the scope of our present moment. What we confront today is not merely politics that borrows from theatre, but a political sphere increasingly conceived as performance and for performance. This represents the first of two qualitative shifts I aim to trace.

The second shift follows naturally: populist performance has gone mainstream. What was once dismissed as fringe – an oddity of fragile democracies, a sideshow that "serious politics" could afford to ignore – now commands the main stage. It appears on the White House lawn, echoes through packed stadiums and airport hangars, and saturates the digital feeds where millions navigate their daily fears and desires.

The U.S. MAGA movement is the obvious marquee act, but Europe has its own ensemble of contenders: Alternative für Deutschland in Germany, Lega and Fratelli d'Italia in Italy, Rassemblement National in France, Geert Wilders' Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, the Reform Party in the UK, and Fidesz in Hungary. Their polling surges and shock victories make headlines, but the more pressing question (at least for the purposes of this project) is what becomes of the performance itself.

The Authoritarian Playbook

Much of the current populist surge in liberal democracies flirts quite openly with authoritarianism. As political theorist Jan-Werner Müller argues in his 2016 book What is Populism?, populists are not just anti-elitist—they are, at their core, anti-pluralist. They insist that they alone embody the will of an imagined, morally pure and unified people – the so called "silent majority" – and in doing so, they inevitably cast all opponents as illegitimate, treasonous, or even "enemies of the people."

Once in power, such claims rarely remain abstract; they tend to crystallise in efforts to bend state institutions to partisan ends, to distribute resources and recognition selectively to those deemed the “real people,” and to curtail the autonomy of civil society—all the while preserving the outward trappings of democracy, whose forms remain intact even as their substance is steadily hollowed out. In this sense, populism transforms democracy into a system where genuine contestation is stripped of legitimacy, and authoritarian practices are recast as morally justified.

As political scientist Larry Diamond (2019), Freedom House (2022) and the V-Dem Institute (2025) have all shown, populist leaders rarely deviate from this script once they take office. Their first instinct is to erode democratic guardrails, steadily concentrating power in their own hands.

The strategies differ depending on the national setting – Orbán tightening his grip through media capture in Hungary, Modi constraining civil society in India, Erdoğan purging the judiciary in Turkey, Trump launching relentless attacks on universities in the United States. Yet beneath these different approaches lies the same underlying playbook: undermine checks, discredit independent voices, and hollow out the institutions that make pluralist democracy possible.

And this is where performance becomes especially revealing. Authoritarian populists must constantly project the illusion of democracy even as they strip it of substance. In countries such as Serbia or Hungary, where democratic backsliding is already entrenched, the formal rituals persist: elections are held, opposition parties campaign, and the media still airs dissenting voices.

Yet these institutions have been hollowed out to the point where they merely imitate pluralism. The familiar spectacle of democracy – the vote, the televised debate, the party congress – can, at first glance, appear authentic. It might even resemble stable democracies marked by long-term single-party dominance, such as Japan.

But the difference is fundamental. In Japan, the ruling party’s continuity rests on voter habit and institutional stability, not coercion; citizens still have the freedom to choose otherwise. In Serbia or Hungary, that choice has become largely symbolic. In Serbia, for example, there isn’t a single municipality run by the opposition, a small but telling sign of how democracy can persist in form long after it has ceased to function.

Governing as Permanent Campaign

The populist who campaigns with a chainsaw soon discovers the limits of his own spectacle. The performance that once thrilled the crowds—the fantasy of cutting through a corrupt system—cannot be postponed indefinitely without exposing itself as mere show. Yet neither can it be carried out in full without dismantling the very machinery that now sustains his power. The result is a paradox he must learn to manage: he cannot deliver on his promise without destroying his own capacity to rule.

What follows is a peculiar kind of theatre, one that must keep replaying its moment of uprising long after the curtain should have fallen. The leader continues to posture as an insurgent while, behind the scenes, quietly and procedurally maintaining the institutions he once swore to upend.

This is where populist performance reveals its true form. The rally never truly ends; it merely changes venue. Governance becomes an extension of the campaign – a state of permanent mobilisation that depends on finding new enemies, new crises, and ever louder gestures to keep the emotional current alive. The chainsaw may no longer appear at press conferences, but its logic lingers: every policy framed as combat, every opponent as an existential threat, every ordinary day in office staged as if the battle for power were still underway.

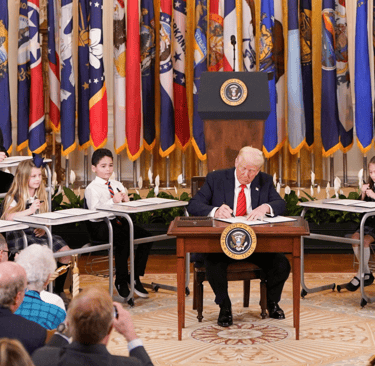

When Donald Trump returned to power in January 2025, his first act was quintessentially performative: a ceremonial signing of executive orders, drawn out into a televised spectacle and broadcast live across sympathetic media networks. The scene bordered on parody: each pen stroke exaggerated, each document lifted theatrically for the cameras.

President Donald Trump signs an executive order in the East Room of the White House directing the dismantling of the U.S. Department of Education, during an event staged as a classroom with students looking on, March 2025. Official White House Photo.

Months into his second term, his reliance on spectacle has not waned despite limited policy success. He now plays the role of peacemaker, obsessively declaring the end of wars—at one point even claiming to have brokered peace between Azerbaijan and Albania, countries that were never at war. The absurdity is beside the point; what matters is the performance—the image of the dealmaker, the strongman who imagines he can bend history to his will by sheer force of personality.

Counter-Staging Democracy

Performance is not just how populists come to power; it's how they reorganise the political stage. What they grasp—better than most seasoned politicians—is that audiences in late democracies are not starved of information but of affect and presence. The technocratic turn in governance, with its reliance on expertise, committee reports, and incrementalism, may deliver policy competence, but it evacuates politics of the visceral charge that makes people feel they matter. Populists flood this void. They don't govern to solve problems; they govern to keep the stage occupied, ensuring that every moment is saturated with their presence, every headline dominated by their voice.

That is the trick: to make politics feel busy enough, loud enough, urgent enough that no alternative production can secure a foothold in the theatre. The problem, then, is not "distraction" – as it is often oversimplified – but monopolisation of attention. Once one actor holds the light, everyone else is pushed into the wings. Democracy, whose form is inherently polyphonic, begins to resemble a one-man show. Pluralism doesn't disappear overnight; it is slowly asphyxiated by a performance so relentless that other voices cannot break through, other narratives cannot take hold, other possibilities cannot be imagined.

Consider Serbia’s Otpor! (Resistance!), the youth movement that helped topple Slobodan Milošević in 2000. When the regime staged grand reconstruction ceremonies to project strength after NATO’s bombing—Milošević casting himself as Serbia’s "great restorer" – Otpor! didn’t bother with policy rebuttals. Instead, they built a miniature Styrofoam bridge in a Belgrade park, claiming it was to “improve accessibility for a group of swans.” When police arrived to dismantle it, the activists turned the scene into a carnival of mockery, transforming the authorities’ overreaction into public farce and leaving the regime looking humorless and absurd, a ruler undone not by arguments, but by laughter.

There are, of course, lingering questions about why humour barely grazes Trump – why ridicule, which once punctured power so effectively, now seems to slide off him without friction. That puzzle deserves its own reckoning, shaped as it is by comedy's migration into the mainstream and its increasingly explicit partisanship. But my concern here is different: that any democratic response to populism worth the effort must move beyond the comfort of familiar arguments and the recycled tactics. It requires counter-staging, the deliberate creation of parallel scenes where the tempo slows, where other bodies can enter the frame, and where alternative stories have space to breathe.